The SAVE plan was created in 2023 as the most affordable student loan repayment option, but a legal challenge led by the state of Missouri has resulted in the plan being temporarily blocked. On December 9, 2025, the Department of Education announced that it agreed to a settlement to end the case, and filed a motion asking for the case to be resolved with an order that the SAVE rules must largely be vacated. This article covers what student loan borrowers – especially the 7 million people enrolled in the SAVE plan – need to know about likely changes coming to the SAVE plan.

Overview

- What does the settlement say?

- Is the settlement final?

- Can I still sign up for the SAVE plan?

- What if I’m already on the SAVE Plan?

- If I’m not enrolled in SAVE and not trying to enroll in SAVE, does this settlement impact me?

- More Information about the SAVE forbearance

- What about the PSLF “buyback” process?

What does the settlement say?

In the settlement, the Department of Education agrees to the following terms:

- The Department will not permit anyone else to enroll in SAVE (or the plan that SAVE replaced, called REPAYE), and it will deny any pending applications for SAVE.

- The Department will work to move borrowers already enrolled in SAVE out of SAVE and into a different repayment plan.

- The Department will not forgive any loans through the SAVE Plan (or through the plan that SAVE replaced, called REPAYE).

- The Department will not implement any provisions of the 2023 repayment rules that created the SAVE plan with one exception: it will implement a provision that allows certain types of deferments and forbearances to count as qualifying time toward loan forgiveness in income-driven repayment plans. This provision is 34 C.F.R. § 685.209(k)(4)(iv).

- The rest of the 2023 repayment regulations, including the SAVE plan, will be vacated, and the Department will conduct a negotiated rulemaking to formally repeal the rules and make further changes to the rules that may be needed.

- For the next 10 years, any time that the Department plans to cancel or forgive more than $10 billion in federal student loans within a one-month period, the Department will notify Missouri.

Is the settlement final?

No. The Department has said that it will not implement the settlement agreement until it is approved by the court. The settlement has been submitted to the court, but as of December 12, the court has not yet acted or set a schedule for when it will.

Can I still sign up for the SAVE plan?

No. The Department of Education stopped allowing borrowers to sign up for the SAVE plan in the Spring of 2025, and under the settlement, the Department would not permit any more borrowers to enroll in SAVE.

What if I’m already on the SAVE Plan?

You likely will not be able to stay in the SAVE plan for long and will likely start receiving student loan bills soon.

Under the settlement, the Department agrees to work to move all of the borrowers currently in the SAVE plan out and into a different repayment plan. The settlement does not say how soon borrowers will have to move out of the SAVE plan. In its press release, the Department of Education said that borrowers in SAVE will have “a limited time” to select a new repayment plan. The Department has not said what repayment plan the Department will move borrowers into if they do not select a new repayment plan.

Borrowers should expect that when they select a new repayment plan — or are switched into a new repayment plan if they do not select one themselves — they will begin receiving monthly student loan bills again and will be expected to make payments. Since summer 2024, borrowers enrolled in the SAVE plan have been in a forbearance, meaning they have not been billed or required to make payments. That forbearance will likely come to an end soon. However, after the SAVE forbearance ends, you can request a temporary forbearance to postpone payments while you consider your repayment options and potentially rework your budget.

Borrowers currently enrolled in SAVE do not have to wait to switch plans. If you are currently in SAVE, you should consider learning more about other repayment options, using the Loan Simulator to estimate your payments in other plans, and potentially applying for a new repayment plan.

But be forewarned – SAVE was the most affordable repayment plan, and your last payments in SAVE were likely based on your income from two or more years ago. Your new payments will most likely be higher in whatever plan you switch to, both because other plans are more expensive than SAVE and because your payments will likely be based on more recent income, which may have gone up. You may want to give yourself some time to rework your budget and consider all of your options before diving into a new plan.

For the most up-to-date information, borrowers should visit the Department of Education’s website.

If I’m not enrolled in SAVE and not trying to enroll in SAVE, does this settlement impact me?

It might. In addition to agreeing not to use the SAVE plan, the settlement also agrees not to implement most of the rest of the changes to the repayment rules made in 2023 – some of which were big improvements for borrowers in all income-driven repayment plans, not just SAVE. For example, as a result of this settlement:

- Borrowers who consolidate their loans now are likely to lose all credit for any time they have already earned towards IDR forgiveness for making payments on their loans prior to consolidating. That means borrowers who consolidate their loans may have to spend more years in repayment as a result of this settlement. (This should not impact borrowers who previously consolidated their loans.)

- Enrolling and staying enrolled in IDR will be more burdensome. The 2023 rules allowed borrowers to agree to data-matching to simplify enrolling and staying enrolled in IDR by allowing the Department of Education to access their income information from their tax filings to set income-driven repayment (IDR) payments, so that borrowers do not have to reapply and submit documentation of their income every year for IDR The settlement would prevent that, and force borrowers to jump through more hoops to manage repayment. The 2023 rules also aimed to reduce defaults by providing for automatic enrollment in IDR for borrowers who fall behind on higher, standard payment amounts; the settlement blocks that as well.

- Borrowers who were steered into forbearances or repayment plans that don’t count towards IDR forgiveness will not be able to “buy back” that past time they missed out on by making additional payments to cover those prior months in nonqualifying status. Note that the settlement does not impact the separate PSLF rules, which will continue to allow borrowers to “buy back” time for purposes of PSLF forgiveness only.

More Information about the SAVE forbearance:

What is the SAVE forbearance?

Borrowers enrolled in the SAVE plan have been placed in a forbearance—meaning borrowers in SAVE are not currently required to make payments. But the Department has started charging interest on these loans again, since August 1, 2025, so borrowers in the SAVE forbearance will see their student loan balances increase the longer they stay in the SAVE forbearance.

Additionally, the months spent in the SAVE forbearance do not count towards IDR or Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), meaning borrowers are missing out on making progress toward becoming debt-free in those programs.

And the SAVE forbearance is likely to come to an end soon, with borrowers required to switch into other plans, after the litigation concludes.

I’ve met the number of payments for IDR cancellation. Can I still have my loans canceled while I’m in the SAVE forbearance?

No. As a result of the litigation, the Department stopped providing IDR cancellation to borrowers enrolled in the SAVE plan, even if they have met the required number of qualifying payments. And in the settlement, the Department agrees not to cancel loans through the SAVE plan. Borrowers in SAVE who have 25 years of qualifying payments (300 months) should consider requesting to switch to the IBR or ICR plans, as they will be eligible to have their loans cancelled in IBR or ICR now. This is particularly important for borrowers who reach 300 months before the end of 2025 because loans cancelled through 2025 will be protected from federal tax consequences. Loans cancelled through IDR after 2025 may be treated as “income” and subject to income taxes.

Note: In October 2025, a court ordered that the Department treat any borrower enrolled in SAVE who reaches 300 months of qualifying IDR payments before the end of 2025 AND who applies to switch to IBR or ICR before the end of 2025 as having qualified for loan cancellation in 2025. This should protect the borrower from having to pay federal taxes on their cancelled debt. If the borrower waits until after 2025 is over, any debt they have cancelled through IDR may be treated as taxable income. Therefore, borrowers in SAVE who have 300 months (25 years) of qualifying IDR payments should strongly consider applying to switch to IBR or ICR before December 31, 2025.

Should I switch out of the SAVE plan now or wait until it’s eliminated?

It depends on your goals, but you might not have long before it is eliminated regardless.

If you want to get your loans cancelled through Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or IDR, it’s important to know that time spent in the SAVE forbearance does not count as qualifying time toward the 10 years in repayment required for PSLF or toward the 20 to 30 years in repayment required for IDR cancellation. Additionally, borrowers cannot make qualifying payments toward IDR or PSLF cancellation while they are in the SAVE plan.

Instead, borrowers who want to continue making progress in IDR or PSLF should consider switching to a different IDR plan, such as IBR, where they can continue earning credit toward IDR or PSLF cancellation. While some borrowers will face higher payments in IBR, PAYE, or ICR, some borrowers who are eligible for $0 payments in SAVE will also be eligible for $0 payments in IBR, PAYE, or ICR. It is worth using the Loan Simulator to check if you are eligible for a $0 payment in other plans and, if not, whether the payments in another plan are affordable to you.

If you can’t afford payments in another plan right now, or need to focus your money on another financial goal (such as paying off a higher interest debt), then it might be fine to leave your loan in the SAVE forbearance for now. Just realize that you might not have much longer before you are forced out of SAVE and into another plan where you’ll have to make payments again. And if you don’t request to switch plans and the Department forces you out of SAVE, it may not switch you to the best plan for you. Additionally, so long as you are in the SAVE forbearance, your balance will go up with interest and you won’t be making progress toward being student-debt free.

What about the PSLF “buyback” process?

There is another option for borrowers in the SAVE forbearance who want to continue earning credit towards PSLF. Some borrowers have been able to get credit toward PSLF forgiveness for time in the SAVE forbearance through the PSLF “buyback” process. The PSLF rules allow borrowers to “buy back” past months that did not count towards PSLF by paying the amounts that they would have needed to pay under an IDR plan during those months. But right now, the buyback process is only available to borrowers who already have 10 years of qualifying employment and will be eligible for cancellation through PSLF now if their past months in forbearance are counted. Borrowers earlier on in their PLSF journey cannot yet use the buyback process.

Also, while some borrowers have reported that the Department allowed them to “buy back” months in the SAVE forbearance by making a lump sum payment for those months based on the same monthly rate that they were paying in SAVE before the forbearance started, the Department may not continue to calculate buyback payments that way. The Department has said this way of calculating buyback rates only applies if the forbearance was less than a year. But the SAVE forbearance has now been going on for over a year. It is therefore unclear how the Department will calculate how much borrowers will owe under the buyback process for months the borrower was in the SAVE forbearance going forward.

For more background about the history of the SAVE plan and the lawsuits surrounding it, see our previous blog posts on this issue.

Did you know that the government can take your tax refund to collect your defaulted federal student loans?

The government has begun seizing tax refunds from borrowers in default for the first time since 2020. It can even take refunds that include thousands of dollars of Child Tax Credits and Earned Income Tax Credits — financial lifelines for working families. Read on to find out how to check if you’re on the list for tax refund seizure, how to protect your tax refund, and how to get your federal student loans out of default.

Generally, federal student loans default after 9 months of nonpayment. There is no time limit on collection of federal student loans, so even if you haven’t heard anything about your loans in a long time, the government could still act to collect your debt.

How can you tell if the government is going to take your tax return to collect your student loan debt? Dial before you file.

Before you file your taxes with the IRS, call the Treasury Department’s Treasury Offset Program Call Center at 1-800-304-3107 to see whether you are on the list to lose some or all of your federal tax refund to collect overdue federal debt.

The government will generally not reach out to tell you that it is going to take your tax refund before it takes it. It may only send one notice when your debt first goes into collection, and many people don’t see it. However, each year, the government creates a list of people who owe the federal government money and who may have their tax refunds taken. The Treasury Department operates the Treasury Offset Program Call Center, a hotline at 1-800-304-3107, that anyone can call to learn whether their name is on the list for some or all of their tax refund to be taken.

When you call, you may not talk to a person. The hotline will ask you to enter your social security number twice to look up whether your name is on the collection list. If your name is on the collection list, the hotline will tell you which federal agency has referred your debt to the Treasury Department for collections. If the Department of Education referred your debt, you probably have student loans in default.

You can double-check if your federal student loans are in default (and get information about who to contact about those defaulted loans) by logging into your account on studentaid.gov. For more information, click here.

If your name is on the list, the government will seize some or all of your tax refund to collect your outstanding debt unless you take additional steps before filing your taxes.

Names can be added and removed from the list, so consider calling to check if you are on the list now and then calling again right before you plan to file your taxes.

Ways You Can Protect Your Tax Refund If Your Name Is On the List

If your name is on the list to have your tax refund seized, you should consider filing an extension to file your taxes before October 15th to give you more time to get your name off the list before filing.

If you are on the collection list because of defaulted student loans, the best way to get your name removed from the list is to get your federal student loans out of default. Getting your student loans out of default can take anywhere from roughly one to ten months depending on which steps you use to remove them from default and how quickly the government processes your requests. Information about your options on removing your loans from default is below. If you file after your loans are removed from default, the government will not take your tax refund to collect your debt.

After getting your loans out of default, call the Treasury Department’s Treasury Offset Program Call Center at 1-800-304-3107 again before filing your taxes to make sure the government has taken your name off the list for tax refund seizure.

Depending on when you act to remove your loans from default, you may not be able to remove your name from the list by the October filing deadline. If you are entitled to a refund and don’t owe the IRS money, you can file your taxes and still get your refund even after the extended deadline in October (as long as you file within 3 years and get your loans out of default before filing). But talk to a tax professional for more information about whether you should wait to file until your name is off the collection list. There could be downsides to filing your taxes late, depending on your situation. If it turns out you actually owe the IRS money, you’d owe a late-filing penalty if you file after the extended deadline.

Note: if you file your taxes jointly with your spouse but only one of you has defaulted federal student loans, consider talking to a tax preparer about whether you can file an Injured Spouse Allocation Form (IRS Form 8379) with your tax return or separately afterwards to protect a portion of your joint tax return.

Steps You Can Take To Remove Your Loans From Default

Apart from fully paying off your loans, there are generally two ways to get your federal student loans out of default:

In addition, you may be eligible to have your loans cancelled through a loan cancellation or discharge program, which would also stop collection.

Each of these options have different pros and cons, discussed below. In addition, you can find more information about each method out of default here.

Consolidation

What is it?

When you consolidate defaulted federal loans, you borrow a new federal loan that pays off the defaulted loans — including any accrued interest, fines, or fees on the defaulted loans. The defaulted loans are paid off and the new consolidation loan is in good standing. Generally, consolidation is one of the fastest ways to get your loans out of default. More general information about consolidation is available here and more information about consolidating out of default is here.

Who is eligible?

Most borrowers with federal student loans in default are eligible for consolidation. The primary reasons you may not be eligible to consolidate loans out of default are:

- If you only have a single Direct Consolidation Loan, then you cannot consolidate it again (unless you also have another loan to consolidate with it).

- If your student loans are currently being collected through wage garnishment or if there is a judgment against you from a federal student loan court case.

Are there downsides to consider?

Yes. If you consolidate your loans right now, there is a risk that you may lose any time towards IDR forgiveness that accrued on your loans before consolidating. So if you’ve spent many years making payments on your loans and are close to having your loans forgiven through IDR, consolidating could delay when your loans are eligible for forgiveness. In addition, if your consolidation loan is disbursed after July 1, 2026, it will have different repayment options than loans disbursed before that date. More information on the pros and cons of consolidating loans is available here and information comparing consolidation to rehabilitation is available here.

How do I consolidate my loans out of default?

To consolidate defaulted loans, you can either log in to your account on studentaid.gov and complete an online consolidation application, or you can submit a paper application. Applying online is generally easier and faster, and has faster processing times and less risk of error. If you submit a paper application, you will also need to submit an application for an income-driven repayment plan and attach documentation of your income, or agree to make three, on-time, full payments before the loan is consolidated. For most borrowers, applying for an IDR plan will be the most affordable and straightforward option.

When you submit a consolidation application, you will need to select which loans you’d like to consolidate: Make sure that you select all of your defaulted loans. You can learn which loans are in default by logging in to your student loan account on studentaid.gov and going to the “My Aid” page and scrolling down to loan details. Loans that are in default will say “default” in the loan status column.

For more information on how to apply for consolidation, click here.

How long does it take for my loans to be removed from default?

Generally, it takes the Department of Education 4-6 weeks to complete a consolidation from the date you apply, but the Department says it can take up to 3 months.

Rehabilitation

What is it?

When you rehabilitate a loan, you make an agreement with your loan holder to make 9 months of full, on-time, reasonable and affordable payments, after which your loans will be put back into good standing. Your loans will not be removed from default until you have made the 9 months of required payments. More detailed information about rehabilitation is here.

Note: If you start making payments in a rehabilitation agreement after January, you may not be able to complete the rehabilitation and remove your loans from default by October (the tax filing deadline if you request an extension). If you make 5 rehabilitation payments before filing your taxes, the Department of Education says that you may be able to stop the government from taking your tax refund — however, there is no guarantee. If you choose to try to protect your tax refund by rehabilitating your loans, then you should make sure to call the Treasury Offset Program Call Center at 1-800-304-3107 before filing to see whether they’ve taken your name off the list for tax refund seizure.

Who is eligible?

Most borrowers are eligible for loan rehabilitation. However, right now you can only complete a loan rehabilitation on a loan once. (Beginning in July 2027, borrowers will be able to rehabilitate twice.) If you started but did not complete a rehabilitation in the past, you can still use rehabilitation to get your loans out of default.

Are there downsides to consider?

Loan rehabilitation takes much longer than consolidation, is more complicated to set up, and requires that you carefully watch your mail so that you can send back the required documentation. If you do not make 9 months of on-time, full payments, your loans will not be removed from default. More information comparing rehabilitation to consolidation is available here.

How do I rehabilitate my student loans out of default?

To start the rehabilitation process, you’ll need to contact the group in charge of collecting on your defaulted loan (often called the “loan holder”). To determine who you need to contact, you can log in to your account on studentaid.gov, or you can call the Default Resolution Group at 1-800-621-3115 and ask who you should contact about rehabilitating your loans out of default. If you have Direct Loans or other loans held by the Department of Education, you will need to talk to the Default Resolution Group to set up a rehabilitation agreement. But if you have other loan types, you may need to call a different phone number.

When you call your loan holder, you can ask to set up a rehabilitation agreement.

Make sure you ask for a rehabilitation agreement — not a payment plan or repayment agreement. Only rehabilitation agreements will remove your loans from default.

When you ask for a rehabilitation agreement, your loan holder will ask you for information about how much money you make so they can determine your monthly rehabilitation payment amounts. They will then ask you to submit documentation, usually your tax filings, proving how much money you make and will send you a written rehabilitation agreement that lists how much you must pay each month in the rehabilitation agreement. You must sign and return the agreement and provide documentation proving your income for your rehabilitation to begin. For more information about what to expect when entering into rehabilitation, click here.

After 9 months of on-time, full payments, your loans will be removed from default and placed back into good standing. It is important that you have a plan for repaying your loans moving forward once your loans are removed from default.

If you cannot complete your rehabilitation agreement before filing your taxes, call your loan holder and see if it will agree to stop collections. It may be possible to stop collections if you agree to rehabilitate soon after receiving a notice of default or after 5 months of rehabilitation payments. However, this may not work in all cases. Before you file your taxes, make sure to call the Treasury Department’s Treasury Offset Program Call Center at 1-800-304-3107 to confirm that your name is not on the list.

Loan Discharge and Cancellation Programs

Federal student loans, including loans in default, can be cancelled (also called “discharged”) in certain situations, such as if you are unable to work due to a permanent disability. If all of your loans in default are cancelled, then you will no longer have loans in default and will not have your tax refund seized.

But it can take months (or sometimes even years) for your loan discharge application to be decided. In some discharge programs, like the Total and Permanent Disability Discharge Program, the government should stop collections (including stopping any tax refund seizures) once it has received your application. However, this is not guaranteed for all discharge programs, and even when it is guaranteed the government might not quickly remove you from the list to have your refund seized. If you have submitted a discharge application, you should still call the Treasury Offset Program Call Center at 1-800-304-3107 to confirm that your name is not on the collection list before filing your taxes. If you are on the list, consider contacting the Default Resolution Group or your loan holder to tell them that you have applied for a discharge and ask if collections can be stopped.

If you have Parent PLUS loans and want access to more affordable monthly payments, you will need to act soon – likely before April 1, 2026. By taking action now, you can make your Parent PLUS loans eligible for an Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan, which sets payments as a portion of your income each year and offers many people lower payments compared to the Standard Repayment plan. But the door is closing: If you don’t act in time, then your Parent PLUS loans will be locked out of IDR plans permanently, which may leave you with unaffordable student loan payments in the future.

Parent PLUS loans are federal student loans taken out by parents to help pay for their child’s education. Not sure if you have a Parent PLUS loan? See how to find out what types of loans you have here.

To make your Parent PLUS loans eligible for an IDR plan, you have to first apply to consolidate your Parent PLUS loans into a new Direct Consolidation Loan. Under a new law, the Big Bill, any Consolidation Loan containing a Parent PLUS loan must be issued before July 1, 2026 to be eligible for an IDR plan. The Department of Education says it typically takes 4-6 weeks for a consolidation to be completed after a borrower submits a consolidation application but can take longer, so it recommends that interested borrowers apply to consolidate by April 1, 2026. You can sign up to repay your Direct Consolidation loan in an Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan, which you must do before July 1, 2028.

What’s the advantage of an IDR plan?

On an IDR plan, each year your student loan monthly payment is set based on your income and family size—not on how much you owe. As a result, IDR payments are often much lower than payments in other plans, especially for borrowers with low incomes or high debts, and payments go down if your income decreases. In addition, in an IDR plan, your loans are canceled after a certain number of years in repayment. Learn more about IDR here.

Here is what you need to know:

1. If you already have a Parent PLUS loan, you must consolidate your loan well before July 1, 2026 – probably before April 1, 2026 – and must enroll in an IDR plan before July 1, 2028 to ensure those loans will be eligible for an IDR plan in the future.

You must take two steps if you want to be able to repay yourParent PLUS loans using an IDR plan now or in the future.

- First, you must apply to consolidate your Parent PLUS loans well before July 1, 2026 – probably before April 1, 2026. Parent PLUS loans consolidated into a Direct Consolidation Loan before July 1, 2026 will be eligible for IDR. To meet that deadline for the new Consolidation Loan, the Department recommends applying to consolidate Parent PLUS loans before April 1, 2026 to ensure your application is processed in time. You can apply to consolidate online here. You can learn more about consolidating your loans here.

- Second, you must enroll your resulting Consolidation Loan in an IDR plan before July 1, 2028, or you will lose the opportunity to enroll in IDR in the future. You can apply to repay your Consolidation Loan in IDR when you apply to consolidate. At first, the Consolidation Loan will likely only be eligible for the Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) plan. But after at least one payment in ICR, you can then apply to switch into the Income-Based Repayment (IBR) plan, which offers lower payments than ICR for most borrowers. You do not have to apply for ICR when you consolidate, but you must apply for ICR and make at least one payment in it before July 1, 2028 or you will lose the opportunity to enroll in IDR in the future.

On July 1, 2028, repayment plans options will change again and the ICR plan will disappear. But if you have taken the two steps above — (1) consolidated your Parent PLUS loans by April 1, 2026, and (2) enrolled in ICR by July 1, 2028 — then you’ll continue to be eligible for IBR, and will be automatically switched from ICR to IBR if you haven’t already switched. This is good because IBR offers lower payments and better terms than ICR for most people.

What if I have already consolidated my Parent PLUS loans?

If you have already consolidated your Parent PLUS loan into a Direct Consolidation Loan, then you do not have to consolidate it again. But if you haven’t already enrolled the Consolidation Loan in an IDR plan (including ICR, IBR, or PAYE), then you must enroll in ICR before July 1, 2028 or you will lose the opportunity to enroll in IDR in the future. Additionally, you should double check that your consolidation loan is a Direct Consolidation Loan. If it is a FFEL Consolidation Loan (only issued before July 2010), then you will likely need to apply to consolidate it into a Direct Consolidation Loan to enroll in IDR. Here’s how you can check what type of loan you have.

2. If you borrow a new Parent PLUS loan or consolidate your Parent PLUS loan and the loan or consolidation is made on or after July 1, 2026, then you will not be able to enroll them in an IDR plan.

The Big Bill changes the repayment rules for all new federal student loans made on or after July 1, 2026. New loans will have to be repaid using one of two new repayment plans:

- the Tiered Standard Repayment Plan, which has fixed monthly payments paid over 10 to 25 years based on the amount you owe, or

- the Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP), a new IDR plan with payments based on your income.

Unfortunately, Parent PLUS loans and Consolidation Loan containing Parent PLUS loans (including double consolidation loans) are not eligible for RAP. Therefore, all new Parent PLUS loans and Consolidation Loans that contain Parent PLUS loans made on or after July 1, 2026 will have to be repaid using the new Tiered Standard plan. This will mean Parent Plus borrowers with low incomes or high student loan burdens will not have a good option to reduce their payments to a more affordable amount.

3. If you consolidate or borrow a new loan after July 1, 2026, then your already existing Parent PLUS loan or Consolidation Loan containing a Parent PLUS loan will not be eligible for IDR.

The Big Bill raises the stakes on borrowing new loans (or consolidating loans) after July 1, 2026 for people who already have loans. If you consolidate or borrow even one loan after that date, then you will have to repay your new loans using one of the two new plans – Tiered Standard or RAP – AND all of your existing Direct loans will have to switch to these new plans. And again, because this deadline applies to the making of new loans, which only happens weeks or months after a borrower has applied for new loans, it could impact borrowers who apply to consolidate after April 1, 2026.

The stakes are especially high for Parent PLUS borrowers, because borrowing or consolidating after this time will mean that even your existing Consolidation Loan that contains a Parent PLUS loan will no longer be eligible for IDR.

This is because Parent PLUS loans, Consolidation Loans containing Parent PLUS loans, and double Consolidation Loans containing Parent PLUS loans are not eligible for the RAP plan. So if you apply to consolidate existing loans or borrow new loans and the loan is issued on or after July 1, 2026, then you will only be able to repay Parent PLUS Loans and Consolidation Loans that contain Parent PLUS loans using the new Tiered Standard plan.

What if I consolidated my Parent PLUS loans before April 1, 2026 to get access to IDR, but then I take out another loan after July 1, 2026?

Unfortunately, if you take out a new loan or consolidate a loan after July 1, 2026, then you will lose access to IDR for any Consolidation Loans you have that contain Parent PLUS loans, even if you previously jumped through all the hoops to make them eligible for IDR. For many Parent PLUS borrowers, this will mean losing access to more affordable monthly payments.

When people think of a typical person dealing with student loan debt, they may not imagine someone over 60. But unfortunately, the student loan debt crisis impacts millions of Americans of all ages, including older people. In fact, people over 60 are the fastest-growing demographic with student loan debt. Millions of older people are struggling with repayment challenges, and it can be confusing to know where to turn.

The AARP Foundation, in partnership with NCLC, has created three new videos to help older borrowers understand their options. These easy-to-understand videos go hand-in-hand with NCLC’s Student Loan Help video series to help borrowers navigate their way out of debt and default.

The new videos from the AARP Foundation and NCLC answer key student loan questions on topics including:

- Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF): Learn how you might be able to get your federal student loans completely forgiven if you work in public service, such as for the government or a non-profit organization.

- Total & Permanent Disability (TPD) Discharge: Find out if you qualify to have your federal student loans canceled if you are unable to work due to a medical condition.

- Getting Out of Default: Learn about the consequences of defaulting on student loans and the steps you can take to prevent collections and get back on track.

Watch free videos from the AARP Foundation and NCLC today to learn your rights and options for dealing with student loan debt.

The SAVE plan was created in 2023 as the most affordable student loan repayment option, but it’s currently blocked by the courts, and Congress decided to eliminate the plan by July 2028. This article covers what student loan borrowers need to know now about the SAVE plan.

Can I still sign up for the SAVE plan?

No. Due to court cases challenging the SAVE plan, the Department of Education stopped allowing borrowers to sign up for the SAVE plan in the Spring of 2025.

What if I’m already on the SAVE Plan?

Borrowers already enrolled in the SAVE plan were automatically placed in forbearance while the court cases are being resolved, meaning these borrowers are not required to make payments right now. Read on for more about the SAVE forbearance.

Additionally, as a result of the Big Bill that was signed into law on July 4, 2025, the SAVE plan, along with a few other IDR plans, will be eliminated for all borrowers by July 1, 2028. Borrowers will not be able to remain in the SAVE plan after that date, and it is possible the plan will be eliminated sooner. Any borrowers still enrolled in SAVE on July 1, 2028 will be automatically switched to a different plan then.

For the most up-to-date information, borrowers should visit the Department of Education’s website.

What You Need to Know if You are Currently on the SAVE Plan:

What is the SAVE forbearance?

Borrowers enrolled in the SAVE plan have been placed in a forbearance—meaning borrowers in SAVE are not currently required to make payments. But the Department has started charging interest on these loans again, since August 1, 2025, so borrowers in the SAVE forbearance will see their student loan balances increase the longer they stay in the SAVE forbearance.

Additionally, the months spent in the SAVE forbearance do not count towards IDR or Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), meaning borrowers are missing out on making progress toward becoming debt-free in those programs.

I’ve met the number of payments for IDR cancellation. Can I still have my loans canceled while I’m in the SAVE forbearance?

No. As a result of court orders, the Department has stopped providing IDR cancellation to borrowers enrolled in the SAVE plan, even if they have met the required number of qualifying payments. Borrowers in SAVE who have 25 years of qualifying payments (300 months) should consider requesting to switch to the IBR or ICR plans, as they will be eligible to have their loans cancelled in IBR or ICR now. This is particularly important for borrowers who reach 300 months before the end of 2025 because loans cancelled through 2025 will be protected from federal tax consequences. Loans cancelled through IDR after 2025 may be treated as “income” and subject to income taxes.

Note: In October 2025, a court ordered that the Department treat any borrower enrolled in SAVE who reaches 300 months of qualifying IDR payments before the end of 2025 AND who applies to switch to IBR or ICR before the end of 2025 as having qualified for loan cancellation in 2025. This should protect the borrower from having to pay federal taxes on their cancelled debt. If the borrower waits until after 2025 is over, any debt they have cancelled through IDR may be treated as taxable income. Therefore, borrowers in SAVE who have 300 months (25 years) of qualifying IDR payments should strongly consider applying to switch to IBR or ICR before December 31, 2025.

Should I switch out of the SAVE plan now or wait until it’s eliminated?

It depends on your goals. If you want to get your loans cancelled through Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or IDR, it’s important to know that time spent in the SAVE forbearance does not count as qualifying time toward the 10 years in repayment required for PSLF or toward the 20 to 30 years in repayment required for IDR cancellation. Additionally, borrowers cannot make qualifying payments toward IDR or PSLF cancellation while they are in the SAVE plan.

Instead, borrowers who want to continue making progress in IDR or PSLF should consider switching to a different IDR plan, such as IBR, where they can continue earning credit toward IDR or PSLF cancellation. While some borrowers will face higher payments in IBR, PAYE, or ICR, some borrowers who are eligible for $0 payments in SAVE will also be eligible for $0 payments in IBR, PAYE, or ICR. It is worth using the Loan Simulator to check if you are eligible for a $0 payment in other plans and, if not, whether the payments in another plan are affordable to you.

If you can’t afford payments in another plan right now, or need to focus your money on another financial goal (e.g., paying off a higher interest debt), then it might be fine to leave your loan in the SAVE forbearance for now. Just realize that your balance will go up with interest, you won’t be making progress toward being student-debt free, and at some point, the SAVE forbearance will end (and the SAVE plan will be fully eliminated), and the Department will start billing you again.

What about the PSLF “buyback” process?

There is another option for borrowers in the SAVE forbearance who want to continue earning credit towards PSLF. Some borrowers have been able to get credit toward PSLF forgiveness for time in the SAVE forbearance through the PSLF “buyback” process. The PSLF rules allow borrowers to “buy back” past months that did not count towards PSLF by paying the amounts that they would have needed to pay under an IDR plan during those months. But right now, the buyback process is only available to borrowers who already have 10 years of qualifying employment and will be eligible for cancellation through PSLF now if their past months in forbearance are counted. Borrowers earlier on in their PLSF journey cannot yet use the buyback process.

Also, while some borrowers have reported that the Department allowed them to “buy back” months in the SAVE forbearance by making a lump sum payment for those months based on the same monthly rate that they were paying in SAVE before the forbearance started, the Department may not continue to calculate buyback payments that way. The Department has said this way of calculating buyback rates only applies if the forbearance was less than a year. But the SAVE forbearance has now been going on for over a year. It is therefore unclear how the Department will calculate how much borrowers will owe under the buyback process for months the borrower was in the SAVE forbearance going forward.

For more background about the history of the SAVE plan and the lawsuits surrounding it, see our previous blog posts on this issue.

On July 4th, President Donald Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill (“Big Bill”) into law. The biggest changes for borrowers include new limits on how much they can borrow in federal student loans, big changes to both current and future borrowers’ repayment options, and changes that will make it harder for borrowers who were harmed by their schools to get debt relief. Unfortunately, for many low-income borrowers, these changes will make paying for college even more difficult. In addition, the bill has changes happening on many different timelines, adding even more complexity to an already confusing system. This blog explains what the bill will mean for current and future student loan borrowers and lays out when those changes will likely occur.

What Does This Bill Do?

- The Big Bill creates a new income-driven repayment plan.

- The Big Bill will end the SAVE Plan and other income-driven repayment plans, leaving only the Income-Based Repayment (IBR) Plan and RAP Plans after July 1, 2028.

- The Big Bill changes borrowers’ repayment options if they borrow any loans after July 1, 2026.

- The Big Bill ends most Parent PLUS borrowers’ access to any Income-Driven Repayment plan.

- The Big Bill Ends the Grad PLUS loan program and creates new limits on how much students and parents can borrow in federal student loans.

- The Big Bill makes it harder for borrowers to get relief after their school closes or their school harmed them.

- The Big Bill will allow borrowers to rehabilitate loans up to two times to remove them from default.

1. The Big Bill creates a new income-driven repayment plan.

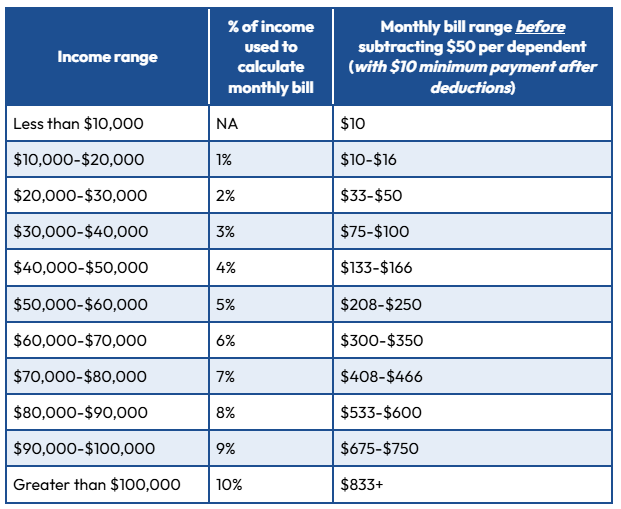

The Big Bill creates the Repayment Assistance Plan, or RAP plan, a new income-driven repayment plan that is very different from the existing IDR plans. Unlike the existing IDR plans, even the poorest student loan borrowers must make a minimum payment of at least $10 a month, regardless of whether or not they fall below the federal poverty line and regardless of their family size. Monthly payments will be calculated as a percentage of the borrower’s total income (using adjusted gross income, or AGI) minus $50 per month per dependent:

Like the SAVE plan, the RAP plan will waive any interest not covered by the borrower’s monthly payment. Additionally, unlike SAVE or other existing plans, the RAP plan will reduce borrowers’ principal by up to $50 if the payment does not do so.

The RAP plan is significantly more expensive for borrowers than the SAVE plan, but will also be more expensive than the other existing IDR plans for low-income borrowers.

Unlike existing IDR plans that provide cancellation after 10-25 years, the RAP plan will only provide cancellation after 30 years of qualifying payments.

The Big Bill specifies that the RAP plan should be available to borrowers beginning on July 1, 2026.

2. The Big Bill will end the SAVE Plan and other income-driven repayment plans, leaving only the Income-Based Repayment (IBR) Plan and RAP Plans after July 1, 2028.

In addition to creating a new IDR plan, the Big Bill instructs the Department of Education to eliminate the PAYE, ICR, and SAVE plans by July 1, 2028 – and it could happen sooner. After those plans are eliminated, borrowers whose loans were all disbursed before July 1, 2026 will have the following repayment options:

- Standard Repayment Plan

- RAP

- Income-Based Repayment (IBR)

- Graduated and Extended Plans

For most borrowers, the required monthly payments in these plans will be significantly higher than payments in the SAVE Plan. This will therefore be an expensive change for many borrowers to deal with.

The Bill makes small changes to the Income-Based Repayment plan so that more existing borrowers will be eligible for it. As a result of the Bill, borrowers no longer have to show that they have a “partial financial hardship” to be eligible for the plan. Additionally, as discussed below, the Bill will allow certain Parent PLUS loan borrowers to enroll in IBR – though they’ll have to jump through hoops first.

Otherwise, IBR remains unchanged for existing borrowers: Borrowers that took on loans before July 1, 2014 will be in “old IBR,” meaning that their monthly payments will be calculated as 15% of any income they earn above 150% of the federal poverty guidelines for their family size (with $0 payments for borrowers who earn less than 150% of the guidelines), and they will receive cancellation after 25 years of qualifying payments. Borrowers that took on loans between July 1, 2014 and July 1, 2026 will be in “new IBR” meaning that their monthly payments will be 10% of any income they earn above 150% of the federal poverty guidelines for their family size (again, with $0 payments for those who earn less than 150% of the guidelines), and they will receive cancellation after 20 years of qualifying payments.

If borrowers enrolled in one of the eliminated plans (SAVE, PAYE, or ICR) do not choose another repayment plan by the time those plans are eliminated, then their Direct Loans taken out for their own education will be placed in the RAP plan and any FFEL loans and any Direct Consolidation loans that repaid a Parent PLUS loan will be placed in the IBR plan.

3. The Big Bill changes borrowers’ repayment options if they borrow any loans after July 1, 2026.

Borrowers that take on any new loan — including borrowers that consolidate an existing federal loan —on or after July 1, 2026 will only be eligible for two repayment plans: the standard repayment plan or the RAP plan.

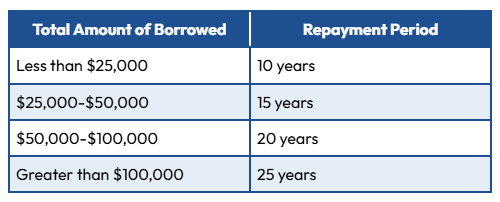

The Big Bill changes standard repayment for loans issued on or after July 1, 2026 and determines the repayment length based on the total amount borrowed.

Borrowers pursuing Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) should note that while payments in a 10-year standard plan qualify for forgiveness, payments in standard plans with repayment periods longer than 10 years do not qualify. As a result, borrowers that take on more than $25,000 in loans after July 1, 2026 will only be able to use the RAP plan to make qualifying payments towards PSLF.

In addition, borrowers that take out loans after July 1, 2027 will not be able to use the economic hardship or unemployment deferments to pause payments if they cannot afford them. In addition, borrowers will only be able to be in many forbearances for up to 9 months during a 2-year period. These new limits on postponing payments in times of financial distress, combined with eliminating $0 payments for new borrowers living in or near poverty, mean that financially distressed borrowers will have fewer options to avoid falling behind and into default.

4. The Big Bill ends most Parent PLUS borrowers’ access to any Income-Driven Repayment plan.

The Big Bill significantly changes Parent PLUS borrowers’ repayment options. Only Parent PLUS borrowers that consolidate their loans before July 1, 2026 and are enrolled in any IDR plan between now and July 1, 2028 will be eligible for an income-driven repayment plan after the SAVE, ICR, and PAYE plans are eliminated on or before July 1, 2028. Those borrowers will be eligible for the Income-Based Repayment (IBR) plan. They will not be eligible for RAP. Existing Parent PLUS borrowers who do not jump through these hoops in time will be locked out of income-driven repayment options, which could make it very difficult to manage their loans if they cannot afford fixed payments.

Borrowers that take on new Parent PLUS loans or consolidate their existing Parent PLUS loans after July 1, 2026 will only be eligible for the new standard repayment plan. If borrowers consolidate or take on Parent PLUS loans after July 1, 2027 those loans will not be eligible for the economic hardship or unemployment deferments and will only be eligible for up to 9 months of many forbearances in a 2 year period. This could mean increased hardship and defaults for low-income Parent PLUS borrowers in the future.

Parent PLUS borrowers should consider consolidating now, before July 1, 2026, and enrolling in the Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) Plan so that they can preserve their ability to make reduced payments in an IDR plan in the future.

5. The Big Bill Ends the Grad PLUS loan program and creates new limits on how much students and parents can borrow in federal student loans.

The bill ends the Grad PLUS loan program, a type of loan for graduate and professional schools that previously allowed students to borrow up to the full cost of attendance, for any borrowers starting a program on or after July 1, 2026.

The bill also adds a number of new limits on how much students and parents can borrow in federal student loans, with limited exceptions for students that have already borrowed loans and are currently enrolled.

6. The Big Bill makes it harder for borrowers to get relief after their school closes or their school harmed them.

Federal student loan borrowers are entitled to loan cancellation in certain situations where their school engaged in misconduct (the Borrower Defense program) or closed before they completed (the Closed School Discharge program). The bill does not end these relief programs, but does make changes to the program rules that will make it harder for borrowers to access relief. Specifically, in 2022, the Department of Education made improvements to the rules for both of these programs to make it easier for eligible students to receive relief. The Bill makes it so that those rule improvements only apply to loans issued after July 1, 2035. That means that existing loans will be subject to the older rules that make it more difficult for borrowers to get relief.

7. The Big Bill will allow borrowers to rehabilitate loans up to two times to remove them from default.

Currently, borrowers can only use a rehabilitation agreement to remove their loans from default once. Starting July 1, 2027, borrowers will be able to use rehabilitation to exit default twice.

What should borrowers do now?

If you have loans now, little is changing immediately — but you should make sure all of your contact information is up to date on studentaid.gov and with your loan servicers, and keep an eye out for coming changes.

While the bill changes student loan borrowers’ rights, the changes won’t happen immediately – most will not happen until July 2026 or later. For now, borrowers’ repayment options remain the same. However, the Department will likely begin changing its student loan rules over the next year, and those rule changes could impact your loan situation. You should make sure that you are receiving up to date information from the Department of Education and from your student loan servicer.

If you are currently enrolled in the SAVE plan, you should also expect that once that plan is eliminated your monthly payments will likely increase. Consider using the Student Loan Simulator to estimate your monthly payment in Income-Based Repayment (IBR), since that plan will remain available to current borrowers. You may want to begin thinking about whether there are changes you can make to your budget to accommodate a higher monthly student loan payment.

If you already have loans, taking on loans (or consolidating) after July 1, 2026 could make your repayment options worse.

Finally, if you have Parent PLUS loans, consider whether it makes sense to consolidate those loans before July 1, 2026 and enroll in the Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) plan to preserve your eligibility to make payments based on your income.

On May 5, 2025, the federal government restarted collections on federal student loans that are in default. That means if you haven’t made a payment on your federal student loans in more than 270 days, you could soon face serious consequences. If you take action now, you may be able to stop or delay collections. Help is available—don’t wait until your paycheck, benefits, or tax refunds are gone!

Watch NCLC’s video on student loans in default now for more information. You can also use NCLC’s Student Loan Toolkit to help you identify what options you may have to deal with your student loan debt.

What can the government do to collect student loan debt?

If you’re in default, the Department of Education can:

- Garnish up to 15% of your paycheck;

- Seize your federal tax refunds;

- Take up to 15% of your Social Security benefits, as long as your remaining monthly benefit stays above $750–the government has said they will not be taking Social Security benefits right now, but this may restart again at any time;

- Send your account to debt collectors; and

- Report negative information to credit bureaus.

Unlike other types of debt collection, the government can take these steps without going to court (in some limited cases, the government may file a lawsuit to collect the debt, but this is not required and doesn’t happen often). There is no statute of limitations on collecting federal student loan debts. This means you could face collection actions for debts that are years old.

Student loan debt collection can hurt your ability to get housing, car loans, or even certain jobs. If you have federal loans in default or are behind on your federal student loan payments, including Direct Loans, Perkins Loans, and FFEL Loans, take steps now to avoid collection.

What should you do right now?

1. Check to see if your loans are in default.

Check if you’re in default on your federal student loan by logging into your account at studentaid.gov. A warning box should appear at the top of your Dashboard letting you know if you have student loans in default. From your Dashboard, you can also click on “View Loans” to review the status of each of your loans to see if you are in default, if you are delinquent (behind on your payments but not yet in default), or if you are in good standing. You can also check the status of your federal student loans by logging into your account with your loan servicer.

2. See if you qualify for loan forgiveness or cancellation.

One way to deal with defaulted student loans is to see if you qualify to have your loans forgiven or canceled through one of the Department of Education’s loan discharge programs. For example, if you are disabled and can’t work, you may be able to have your loans canceled and discharged, even if they are in default, through the Total and Permanent Disability Discharge Program. See our page on cancellation and forgiveness options, or watch this video to see if you qualify.

3. If you are in default, take steps to get out of default.

If you are in default, look at options for getting out of default. Right now, there are only two real ways to get your loans out of default if you cannot afford to pay the loans in full. You can either complete a loan rehabilitation or consolidate your loans to get them out of default. Once you are out of default, make sure to sign up for an income-driven repayment plan (IDR) if you can’t afford the standard repayment and want to avoid falling behind on your loan payments again. Watch our video on dealing with default for more information.

4. If you aren’t in default, but you are struggling with payments, consider signing up for an IDR plan.

If you are not yet in default, but you are struggling to afford your loan payments or are delinquent, look into an income-driven repayment (IDR) plan. Your payments could be as low as $0 per month, and you could earn credit toward loan forgiveness while in an IDR plan. If you can’t afford an IDR plan, consider a deferment or forbearance to temporarily pause your student loan payments. Watch our video on different options for managing your student loan repayments.

5. If you got a notice of an upcoming collection action, review your options for stopping it.

If you’re facing a collection action that you don’t agree with, such as a tax refund or Social Security benefits offset, you can either challenge the debt if you believe it’s invalid or already paid, or request a financial hardship review if you can’t afford collections and are facing some serious financial hardship such as an eviction, utility shut-off, or forclosure. The steps to try to stop a collection action may be different depending on what type of collection you’re facing. The government may also be changing the way it collects and manages student loan defaults in the future, so make sure to check the Federal Student Aid website page on collections for updates on the process.

Note: It can be difficult to stop a collection action from happening, so you should still look at other options to get out of default to avoid any more collections from taking place. For more information, visit the Federal Student Aid website’s collections page.

On April 25, we published this story urging borrowers to screenshot their IDR progress tracker in case the government removes this important information. On April 28, the government removed the tracker. You may still be able to access your IDR payment count by logging into your studentaid.gov account and navigating to https://studentaid.gov/app/api/nslds/payment-counter/summary.

In January, we shared that the Department of Education had added important new information to studentaid.gov showing borrowers their progress toward being debt-free through Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans. As we reported, borrowers could log into their accounts on studentaid.gov and see an IDR progress tracker showing how many months of qualifying payments they had made in IDR. They could also see how many more years and months of payments they would need to make until they would be eligible to have any remaining loan balance cancelled.

However, recently we have seen the federal government remove lots of information from government websites, and this IDR progress tracker could be removed at any time. Borrowers should therefore save this information while they can, in case it is removed from their accounts. Do it today!

Why save the IDR progress tracker? If the IDR progress tracker is removed from borrowers’ accounts, it will be much harder for borrowers to make informed decisions about how to manage their loans. For example, right now, if you consolidate your loans your consolidation loan will start with no months credited towards IDR forgiveness, regardless of how long you were in an IDR plan previously. Without the tracker, it will be difficult for borrowers to know how much time toward cancellation they stand to lose.

The tracker also helps borrowers see how much time remains until their loans are eligible for cancellation in an IDR plan. Removing the tracker would make it harder for borrowers to make sure they actually get their loans cancelled when they are eligible for cancellation, and to dispute any mistakes the government or their servicers may make by failing to credit borrowers for qualifying time in repayment.

We are encouraging borrowers to screenshot their IDR progress tracker on studentaid.gov and to save it as soon as possible. Here’s how to do it:

- Log into your federal student aid account on studentaid.gov.

- You should now see your “student aid dashboard.” On the right hand side of the screen, there is a new section showing you how much time is left until the IDR End of Payment Term. This is how many more years and months of qualifying payments you will need to make before you qualify to have any remaining balance on your student loans canceled. Below is an example of what you are looking for on your dashboard:

- Take a screenshot of your dashboard that includes this IDR End of Payment Term information and save it to your files. (Or print the page to PDF and save to your files.)

If that’s all you have time or energy to do, stop there. But if you want to have records of all of your qualifying months of payments, and especially if you attended school during different time periods and have multiple loans that have different payment counts, continue with the following steps to save more of your information. This additional information will put you in the best position to protect the progress you’ve already earned against any attempts to take it away or any servicer mistakes.

- Click on “View IDR Progress,” which will take you to a page where you can see your qualifying payment count for each of your federal student loans. Under “Qualifying Payment(s)” you will see, for each of your loans, how many qualifying payments you have already made toward qualifying to have the remaining balance of your loan cancelled via IDR. Again, consider saving screenshots, or printing to PDF and saving to your records. An example is below:

- Next, click “Payment History.” This page will show you, for every month since you started repaying each of your loans, whether the Department recorded that month as a “qualifying” payment month toward your IDR payment term, vs “ineligible.” An example is below. Screenshot (or save as PDF) the full payment history for each of your loans for your records. Only ten entries may show up at a time, so make sure you take a picture of each page of payments.

We hope that the Department will not take this critical information away from borrowers, but it is best to be prepared in case it does.

Are you enrolled in IDR and working towards being debt free? Share your story.

This week, the Department of Education announced that it plans to begin forced collection on federal student loans that are in default as soon as May 5, 2025. That means it will begin seizing money from some borrower’s tax refunds, Social Security benefits, and – later this year – paychecks.

Starting forced collections will be a big change: collection has been paused for most borrowers since March 2020. And with more than 5 million people currently in default and thus at risk of forced collections, a huge number of people across the country stand to suddenly see a big hit to their pocketbooks.

The government only uses forced collection against loans that are in default. Loans generally default after 270 days of missed payments. However, during pandemic payment pause and other temporary relief programs in effect from 2020 until 2024, most collections were paused and missed payments generally did not put loans closer to defaulting. As of now, 5.3 million people have federal student loans in default, and another 4 million are at risk of defaulting later this year.

But there are things borrowers can do to protect themselves. Below, we share what we know about the government’s plans to begin forced collections. Then we walk through options borrowers have to protect themselves against forced collections and to manage their student loan debt.

The Government’s Plan To Begin Collection of Defaulted Student Loans

The Department’s announcement says that it plans to start forced collection using the Treasury Offset Program beginning May 5, 2025. It says it will not begin garnishing paychecks until after sending out garnishment notices “later this summer.” When it does, it can seize up to 15% of borrowers’ paychecks to pay off federal student loans in default.

The Treasury Offset Program takes money from tax refunds and certain government benefits (the biggest being Social Security retirement and disability benefits) to collect on defaulted debts owed to the federal government.

- Tax refund seizures: The government can seize a borrower’s whole federal tax refund (and, in some states, their state refund) to collect on a defaulted federal student loan. The only limit is that the government can’t seize more than the total amount of the debt. The government can only seize a tax refund that hasn’t yet been sent to the taxpayer – if you’ve already gotten your refund this year, then you should not be at risk of any tax refund seizure until 2026.

- Social Security seizures: The government can take up to 15% of monthly Social Security retirement and disability benefits to collect on a defaulted federal student loan. In January, the Biden Administration announced that to prevent student loans from pushing people into poverty, it would protect 150% of the federal poverty level (about $1,883 / month) in Social Security benefits from seizure. But we do not yet know if the Trump Administration will honor that commitment to protecting Social Security benefits.

We do not yet know if the government will begin seizing tax refunds and Social Security benefits immediately on May 5, or if borrowers will have a couple more months before that happens. Generally, the Department must provide notice that it is going to start forced collection against a borrower and provide them time to object or remove their loans from default. Under the Biden Administration, the Department said that it would provide legal notices to borrowers already in default and would not begin seizing tax refunds or Social Security benefits for at least two months until after the notices had been sent. But the Trump Administration has not said whether it will do this, so it is unclear whether the government is going to provide notice and the opportunity to object to all borrowers before collecting, or whether it will only provide notice to those who are newly in default and were not subject to collections before the COVID-19 payment pause began.

Regardless, for borrowers in default who have not yet received their tax refunds this year, or who rely on Social Security benefits, acting fast is the best way to protect these payments from being seized.

What Borrowers Can Do To Protect Themselves

1. Find Out if You Have Student Loans in Default

The first step to protecting yourself against forced collections is to figure out if you have any federal student loans in default. The best way to do this is to log into your account on the Federal Student Aid website, studentaid.gov. There you’ll find a dashboard with your loan information, including how much you owe and the status of your loans (in repayment, grace period, forbearance, deferment, delinquent, or in default). If you’re in default, you may also see a warning that says so at the top of your account dashboard. For more about understanding your loan information, see here.

If your loans are currently in default, you may face collections as soon as May. And if your loans are delinquent, they may default after 270 days of delinquency.

Federal student loans become delinquent after a missed payment. After 3 months of missed payments, the delinquency is reported on your credit reports. Then, after 9 months of missed payments, loans go into default. However, you have options when your loans are delinquent that will prevent them from going into default. You should consider using forbearances or deferments to bring your loans current and you can apply for an IDR plan to make payments more affordable in the future.

The Department of Education said that it would be emailing borrowers in default over the next couple weeks. But don’t rely on receiving an email – the Department does not have email addresses or other contact information for all borrowers in default. (To update your contact information, go to studentaid.gov and update it there AND contact your loan servicer to update your contact information with them.)

Share Your Story: Many borrowers are doing their best but find themselves in default when they can’t afford student loan payments following a medical issue, job loss, divorce, or withdrawing from school, and aren’t told about options to reduce or postpone payments. Share your story about how you wound up in default or how default has impacted you.

2. Figure Out if You Are Expecting Payments That Could Be Seized

Your situation will be most urgent if your loans are already in default AND if you are expecting to receive the type of payments that the government may begin seizing first. The most common payment types that could be seized first are:

- Social Security: If you receive Social Security disability or retirement benefits, those may be at risk of partial seizure soon. That’s a good reason to act now. (Supplemental Security Income, or SSI, is protected from seizure.)

- Tax refunds:

- If you have filed your taxes and are expecting a refund that you haven’t received yet, that refund could be at risk of seizure – a good reason to act now.

- Similarly, if you haven’t yet filed your taxes this year and expect a refund when you do, that refund could be at risk of seizure. You might consider requesting an extension and waiting to file until after you have addressed your loan default.

- On the other hand, if you have already received your tax refund this year, or aren’t due a refund, then you are not at immediate risk of having your refund seized. What you’ve already received is safe. It wouldn’t be until when you file taxes next year that you would face tax refund seizure.

If you are not expecting a tax refund or Social Security payment, then you should have more time to address your loan default before wage garnishments begin later this year.

3. Consider Options to Discharge (Cancel) Your Student Debt

If you have a federal student loan in default, you should consider whether it’s eligible for cancellation through one of the current discharge programs. For example, you may be able to cancel your federal student loans if:

- you have a serious disability that prevents you from working;

- your school closed before you completed your program;

- your loans were taken out in your name without your knowledge;

- your school lied to you about important information about the program you would attend, the outcomes of graduates, or the type of federal aid you’d receive, or they engaged in aggressive and deceptive recruitment.

For more information about discharge programs, and how to apply, see here. You may be able to apply to cancel your loans through one of these programs and request to have collections stopped on your loans while your application is considered.

Additionally, you may be eligible to have your student loans discharged through bankruptcy, but doing so is difficult. And it is often considered a last resort because it impacts your credit and involves a lot of time and expense. Bankruptcy may still make sense for some borrowers; more information is available here.

4. Consider Options to Get Out of Default – And to Stay Out of Default

If you’re in default but you are not eligible for a loan discharge, then you may want to get your loans out of default to prevent or stop forced collections. Getting your loans out of default has other benefits too, including improving your credit and restoring your eligibility for federal student aid if you want to go back to school.

There are generally two ways to get out of default: consolidation and rehabilitation.

- Consolidation means taking out a new federal Direct Consolidation Loan to pay off your defaulted loans. It is generally the fastest and most straightforward way to get out of default (and can be done online at studentaid.gov), but there are some downsides. One downside is that, as a result of a recent change in approach, you will lose any credit you have earned toward having your loans forgiven in an income-driven repayment plan. You may be able to see how much credit you could lose by logging into studentaid.gov and looking for the “End of IDR Payment Term” information on your dashboard.

- Rehabilitation means entering into a rehabilitation agreement with your loan holder and making nine months of on-time payments in amounts set based on your income. If you successfully complete the rehabilitation, then your loans will be removed from default and put back in repayment. Rehabilitation takes much longer than consolidation, and if forced collections begin on you before you enter a rehabilitation agreement, then collections may continue for months while you make rehabilitation payments.

There are pros and cons to each option, and the Department of Education has a comparison chart and more details here. Additionally, borrowers should be aware that you are generally limited to only using each option once, so not all borrowers will be eligible to rehabilitate or consolidate out of default.

Whichever path you choose, you will want to avoid defaulting again after getting your loans out of default. For most borrowers, the best way to do that is to enroll in an income-driven repayment plan (which may offer payments as low as $0 / month) or to make use of forbearances and deferments that temporarily postpone payments during periods you can’t afford to pay.

5. Other Ways To Protect Yourself from Collections

If you aren’t eligible to have your loans cancelled and you can’t get them out of default through consolidation or rehabilitation, there may still be something you can do to protect yourself from forced collections.

For example, if having money taken from your Social Security benefits would prevent you from being able to pay your living expenses, you can request relief from Social Security seizures based on financial hardship.

Or, it is possible that the government’s information is wrong and your loans should not be in default, or the amount they are claiming you owe is wrong, or you should be temporarily protected from collections (often called “in stopped collections”) because you have applied for a discharge. You can request to review your student loan records and you can raise an objection to collection. For more information about how to request your records and object to collection, see here.

Are you at risk for forced collections after struggling with student loan debt? How could it impact your family? Share your story.

On March 26, 2025, the Department of Education reopened the online application for Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans for federal student loan borrowers. Borrowers can now apply to enroll in, switch between, or update their income in IDR plans at studentaid.gov.

This follows a very stressful period for student loan borrowers. On February 21, the Department pulled down the IDR application. The Department said it was doing so in response to a recent court order in a lawsuit challenging the SAVE plan, but did not tell borrowers how long it would be down, what was changing, or what their options for managing their loans would be. This created widespread confusion and financial stress for people trying to sign up for IDR or keep their payment amounts affordable in IDR.

The online application is now back up, but there are some important changes that borrowers need to know about. Significantly, borrowers can no longer sign up for the SAVE plan on the online application. This blog post will cover what borrowers need to know now that the IDR application is back up, including:

- Changes to the IDR Application

- Delays in Processing Applications

- Annual Recertification Deadline Changes

- Consolidation Application is Back Up – But Beware

- Other Changes and the Department’s Explanation

Open Question: What will happen to borrowers who previously applied for SAVE or the plan with the lowest monthly payment and whose application wasn’t been processed?

What Borrowers Need to Know Now

Changes to the IDR Application

The online IDR application is now available to borrowers again. The paper/PDF application is not yet available as of March 27, but should be posted here (under “Loan Repayment”) when available. [Update 4/9/25: The paper/PDF application is now available.]

The Department made changes to the IDR application. The biggest changes are to the plans the borrower can request:

- The IDR application no longer allows borrowers to sign up for the SAVE plan.

- The IDR application no longer allows borrowers to request to sign up for the IDR “plan with the lowest monthly payment.” Prior versions of the IDR application listed this option first and noted it was “Recommended.” This was a useful option to borrowers as it allowed them to enroll in IDR without having to worry about the details of each of the four IDR plans to figure out which plans they were eligible for and which plans would be best for them.

Open Questions: